The “How” of Composing from a Model

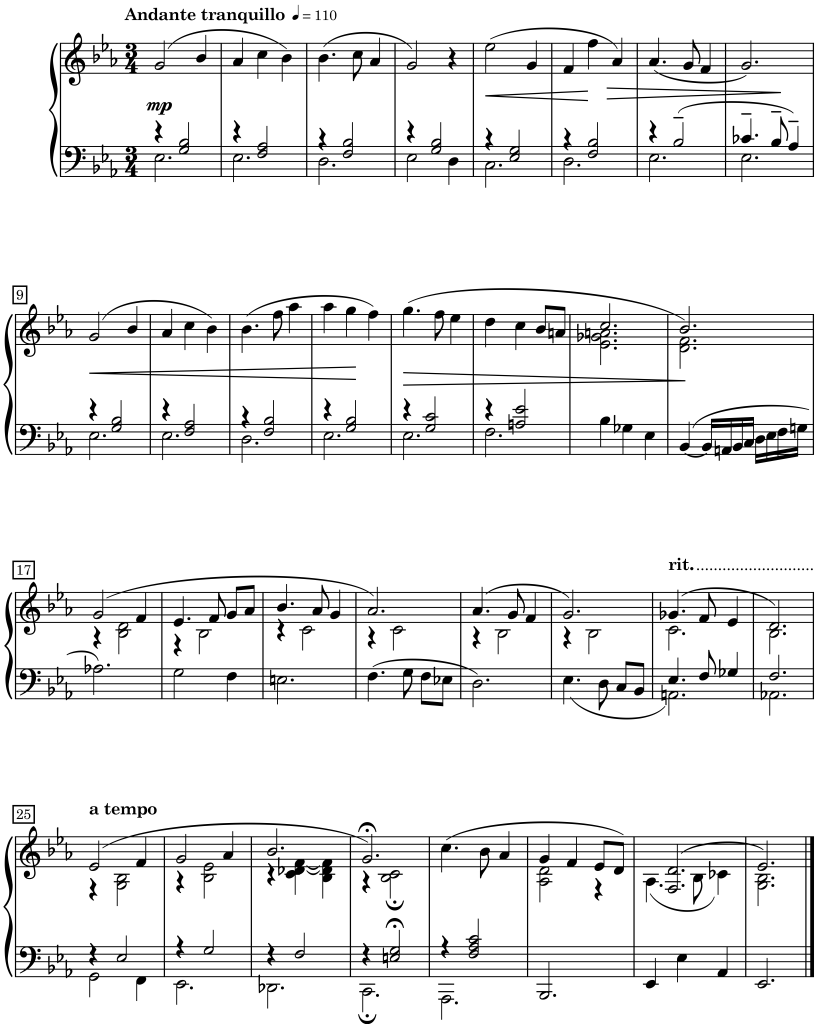

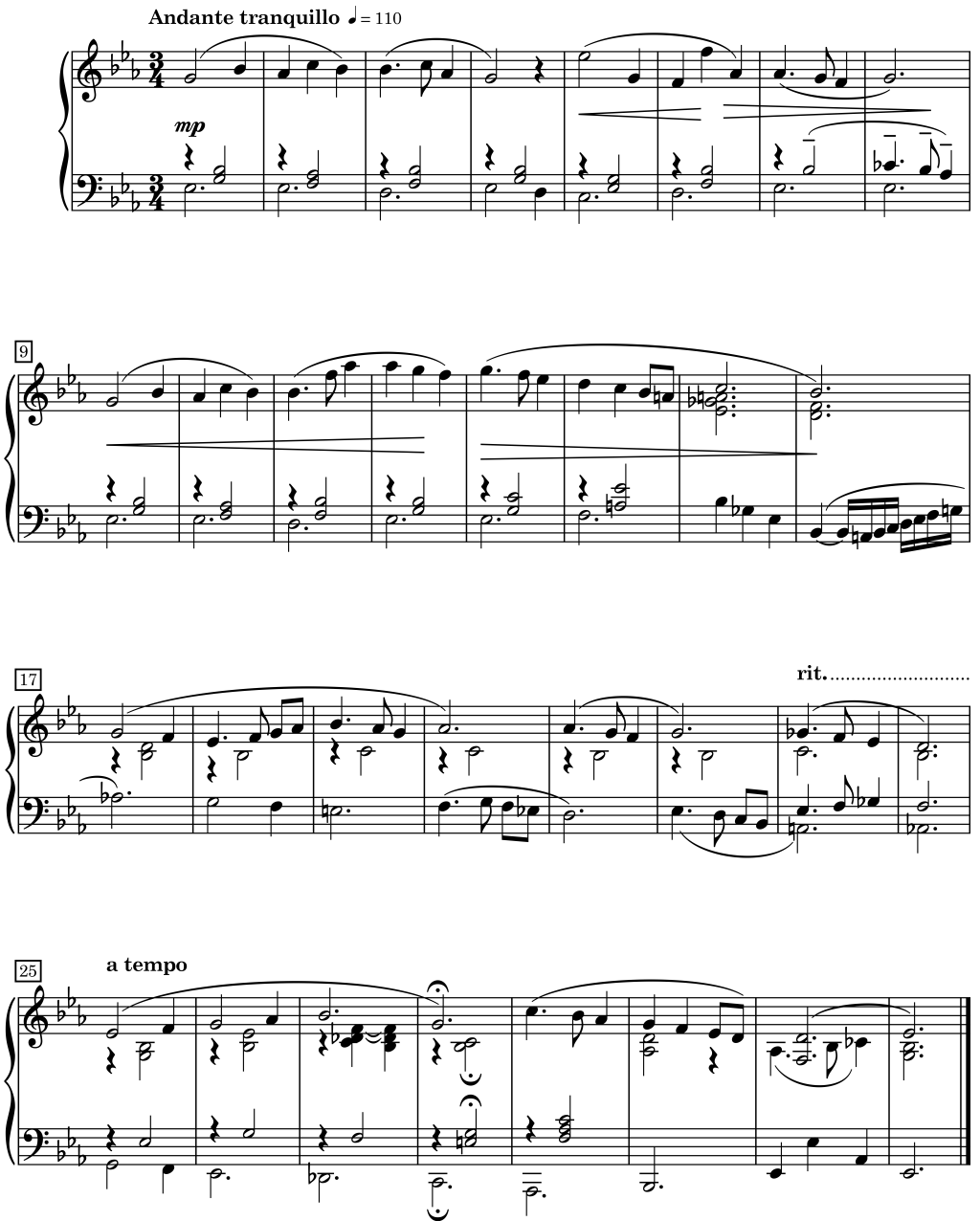

I submit for your consideration the following short piano piece:

This is not in any way a grand masterpiece. It is short, quaint, and technically undemanding. Perhaps it has some charm, but only in the environment of a relaxed evening spent playing through an anthology of enjoyable but nondescript piano pieces. It would be right at home in the collections of any number of forgotten 19th-century composers. It is by definition a bagatelle–a trifle. But it is my trifle, and I would like to show you how I composed it.

I used an approach that I teach to my more advanced students. The whole process took me only a couple of hours. I followed these steps:

1. Choose a simple piece that can be analyzed quickly.

2. Reduce the piece to its most salient features (bass and simplified melody) and label it with figured bass.

3. Make small changes to the harmony according to personal taste.

4. Craft a new melody that aligns with the new harmony.

5. Add inner voices as appropriate.

Let’s look at each of these steps in greater detail.

1. Choose a simple piece that can be analyzed quickly.

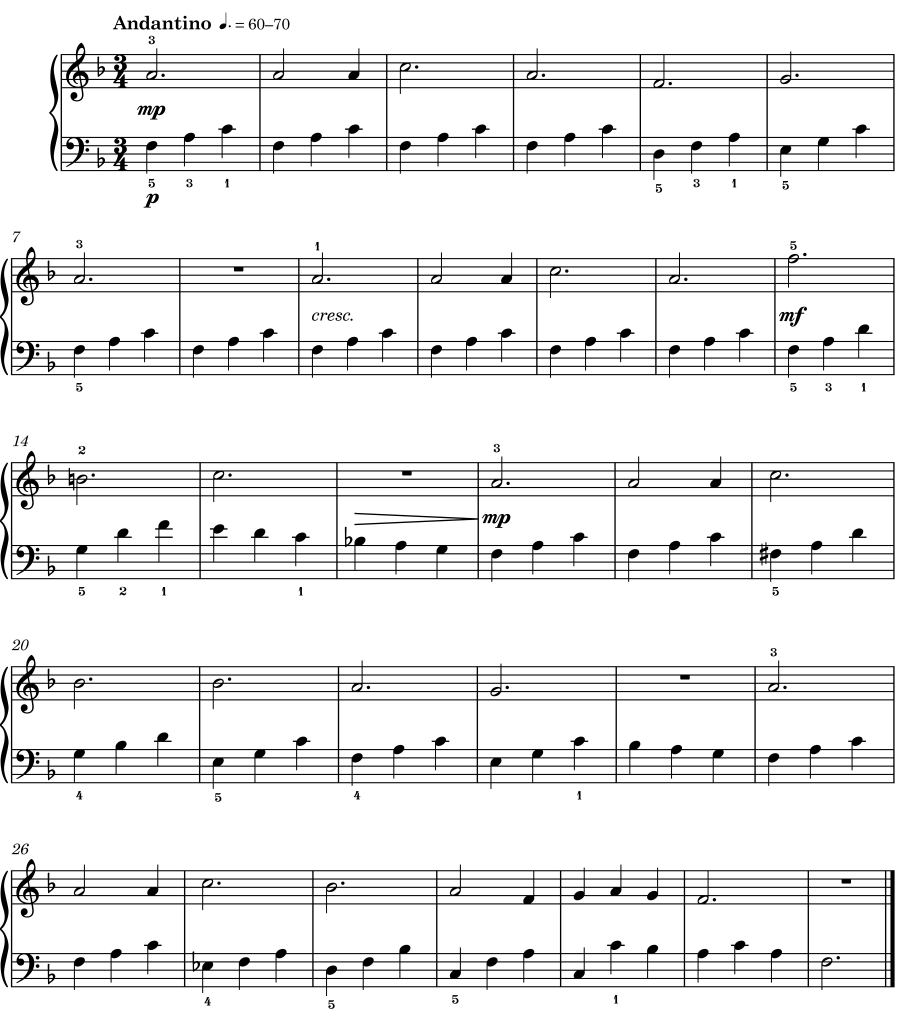

Most student composers who are convinced of this approach nonetheless make their first mistake by trying to model their own composition after some large-scale work by a master composer: a Beethoven sonata movement, a Bach fugue, or maybe a Chopin etude. These are superb models, and they have their place. But for a first attempt, the simpler the piece, the better. I chose Louis Köhler’s Etude in F major, Opus 190, Number 27. This piece is currently in the Royal Conservatory’s Level 2 anthology of etudes. I first notated the etude for my own working edition, reprinted below. A free version of the piece can be found on imslp.org.

This piece consists of four 8-bar phrases. The left hand moves in constant quarter notes until the very last measure while the right-hand melody moves primarily in dotted half notes with the occasional trochaic rhythm. The melody’s apex occurs in measure 13, which, when combined with the bass, gives the piece a maximum range of two octaves plus a fourth. The harmony is mostly diatonic, with short tonicizations to the dominant, supertonic, and subdominant.

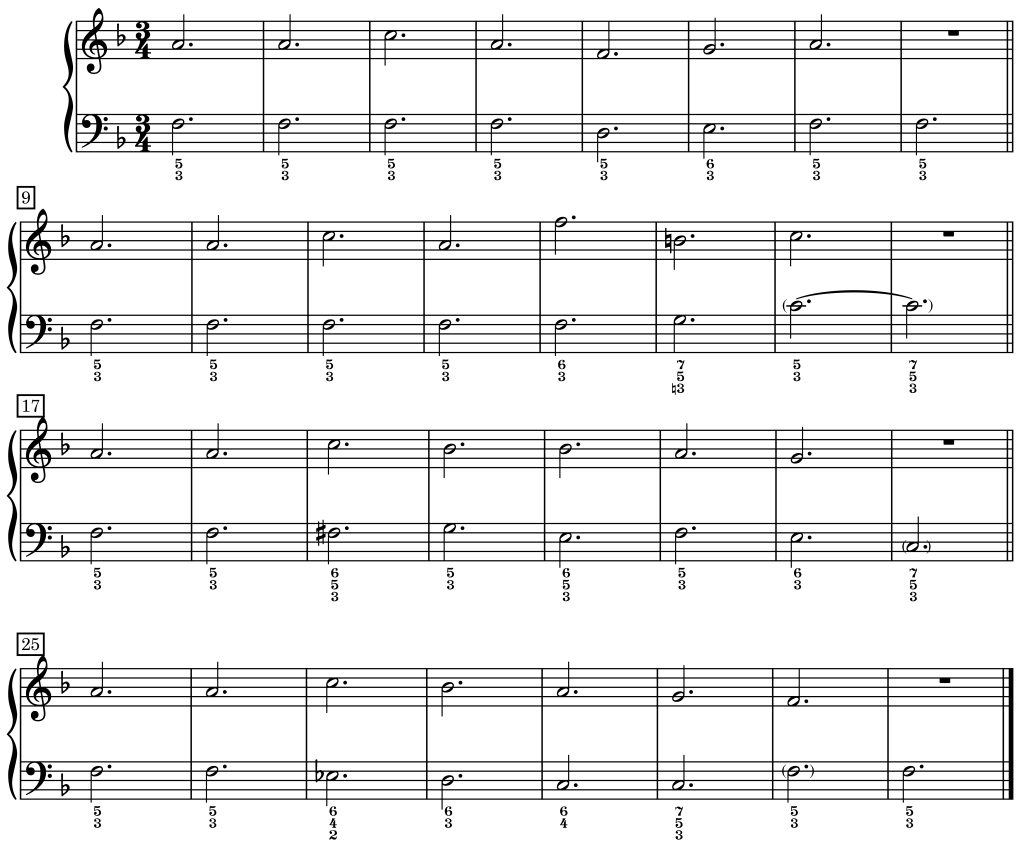

2. Reduce the piece to its most salient features (bass and simplified melody) and label it with figured bass.

With such a simple melody, the reduction of this piece was straightforward. Because of the relatively diatonic harmonic language, the figured bass also proved to be quick work.

When examining this reduction, it is already easy to see (and hear) some places where the simple harmony can be made more complex. This simplicity is not a fault of Köhler’s; this etude comes from a book of pieces designed for beginners, and he is doubtless keeping the language accessible to young players. In fact, this is a good lesson for students to learn early on: simple can be quite effective. However, since my intent was not to write a piece for beginners, I wanted to increase the harmonic complexity.

3. Make small changes to the harmony according to personal taste.

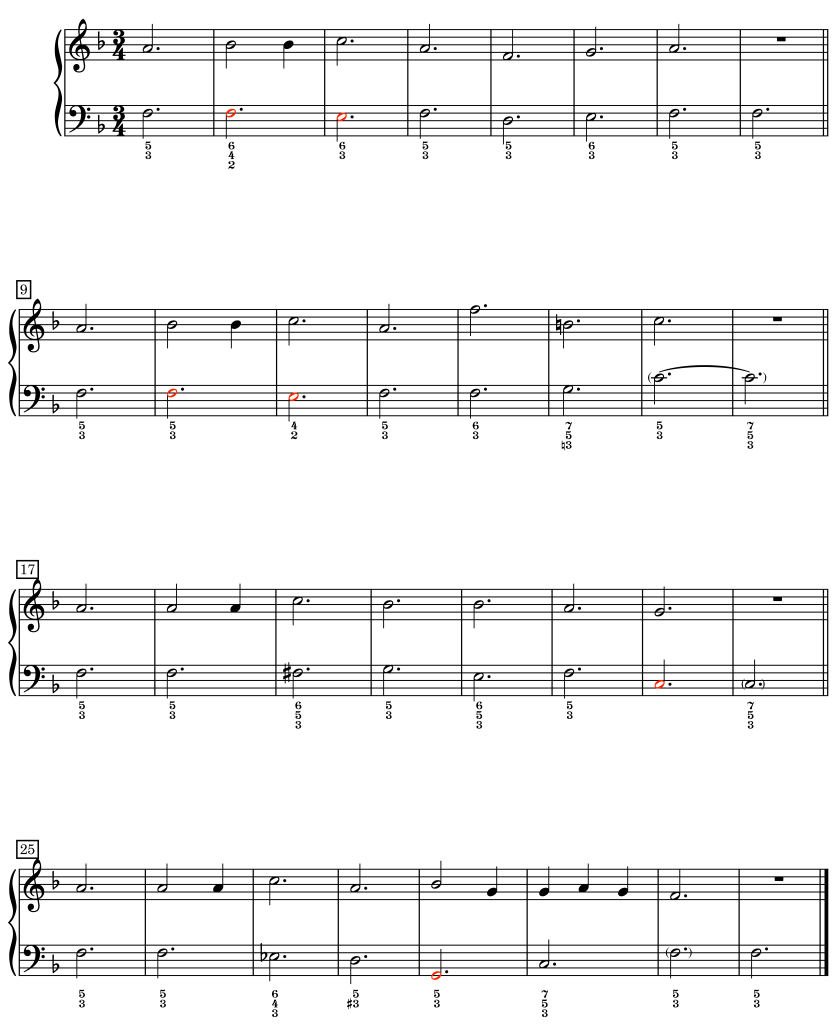

This can be the most enjoyable step in the process. At this point, with the reduced model serving as the sketch, I experimented with other harmonies, attempting to introduce more subtleties into the bass motion. Below is the reduction with my alterations notated in red.

In Köhler’s original, the first four measures consist of the same tonic harmony. I viewed this as an opportunity to replace this with what is commonly referred to as the “Page One” schema. This gives more harmonic motion at the onset and provides the possibility for a more intricate melody. I repeated this schema in the analogous passage in measures 9-12. In measure 23, I chose to increase the strength of the half cadence by putting the dominant harmony in root position. I gave the same root position to the supertonic in measure 29.

It is important to remember that these changes are not written in stone. They can be further changed or even reverted in later steps. Likewise, other possibilities may present themselves as the melody is fleshed out. In fact, you will see both changes and reversions in the next steps.

4. Craft a new melody that aligns with the new harmony.

This step requires the decoration of the skeleton melody. Much of this step is intuitive and is therefore difficult to methodize. A good resource for decoration, however, is the textbook Harmony through Melody by Horton, Byrne, and Ritchey. I teach students cantus decoration using their approach, so I used the same approach here.

I will not detail every decision in this melody writing process, but some important points warrant mention.

1. The dactylic rhythm first introduced in measure 3 became a prevalent feature throughout the melody.

2. Treating the first 16 measures as a period, I aimed to provide a pleasing contour culminating in an apex around measure 12.

3. I introduced diminished harmonies in measures 15 and 23 in order to give this piece a more Romantic period feel.

4. I began to provide harmonic detail at certain points, much like an artist will add intermittent detail while building a sketch into a final drawing. This detail can be seen in the third phrase.

5. Notice that I decided to change the bass in measure 17 to allow for a stepwise motion down to the F-sharp in measure 19. I also reverted the supertonic in measure 29 to a 6/3 chord.

6. At this point in the process, I was still unsatisfied with the harmony (rather, the contrapuntal delivery of the harmony) in measures 25-28. However, I still wanted to maintain the Phrygian motion in measures 27 and 28. This would be solved in the next step.

5. Add inner voices as appropriate.

Once the harmonic framework and melody were decided, it was time to flesh out the harmonies with inner voices, decorate the principal voices, and provide thematic unity through the use of rhythmic motives. At this point, I decided to improve the harmonic motion in measures 25-28 by changing the tonic harmony in measure 25 into a 6/3 chord. This necessitated a change in the melody and prevented me from calling back to the original idea used by Köhler, but this was a small price to pay. The further use of a fermata in measure 28 allowed this fourth phrase to anticipate the final cadence.

One final step (one that is possibly insidious) was to transpose the piece to a new key. This is recommended if one wants to hide one’s tracks. Because I did this after the bulk of the composing was finished, I decided it was best to choose a key geographically close to F major. A word of caution, though: I could make this decision towards the end because the piece is melodic in nature and relatively slow in tempo. Had this piece been centered around figurations or involved intricate and quick-moving passagework, I would have needed to factor in the key early in the process.

Hopefully, this gives you some compositional inspiration. If you’re not convinced, a future post will explore the “why” of composing from a model, in which I will explain the advantages of such a technique and address some of the objections.

Leave a comment