On Friday, August 6th of 2021, I slowly sat down at my piano, put my phone on the music rack in front of me, and wept bitterly. The sudden reality of the emotion shocked me, and the fact that I was alone brought out a level of authenticity for which I was extremely unprepared.

“Apparently Mr. Avalon was in a car accident and died a few weeks ago.”

The text message had been from my wife. She had gone out to dinner with some coworkers, one of whom who had recently moved from my home state of Mississippi. They had been catching up on all the news from Madison, the city in which Kristy and I lived shortly before coming to Atlanta. The most pressing, and tragic, news was of the passing of William Vance Avalon, a beloved man of the community who had shaped the lives of countless people.

I spent the next several hours trying to unravel what it was, specifically, that had struck me so powerfully upon learning of his death. We hadn’t stayed in touch, so we weren’t especially close. Maybe that was it? I had always meant to reach out and tell him what an influence he had been to me, and now that opportunity was gone. Then again, his was the most recent in a long line of deaths that served to remind me that there are some homes to which you can never return. This is my attempt to understand those emotions. What follows may not be overly structured, but it is the kind of organicism born of grief. Sometimes, all that is left is to mourn and reminisce.

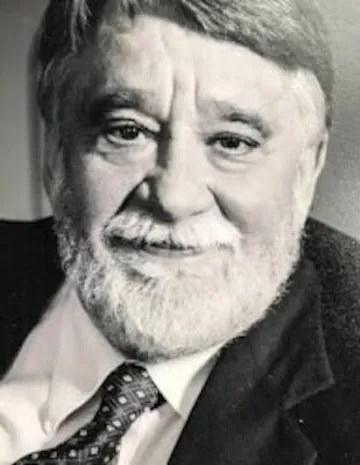

I remember Mr. Avalon as an endearingly misanthropic character. When I knew him, he was a pack-a-day smoker whose greying mustache was stained Nicotine Brown—but only beneath his nostrils. My friends and I used to joke that he resembled a slightly more corpulent Kurt Vonnegut—an image I am convinced he deliberately cultivated. Others likened him to a domesticated grizzly bear. If you object that grizzlies are never really domesticated, I’ll tell you that’s the point. His gruff voice was always offering a sarcastic “Hey-a, buddy!” or “Hmph! Monosyllabic grunt!” or (his favorite) “You’re a great American.” Everyone whom he held in high esteem was a great American, regardless of actual nationality. Even the Bohemian author Franz Kafka was a great American.

It was Mr. Avalon who introduced me to Kafka, and as a 17 year old full of angst and a perpetual sense of injustice, I was entirely open to reading an author he described as “an innocent man guilty of everything.” Of course, my first exposure was “The Metamorphosis”, but within a year I would end up reading everything Kafka wrote. For me, I can’t think of Kafka without seeing Mr. Avalon chuckle at the ridiculous plight of Gregor, or Josef K., or even Kafka himself. So, on that Friday night, after half-heartedly starting and stopping a dozen piano pieces in an effort to distract myself, I finally got up and went to the couch to re-read “The Metamorphosis”.

Now, I am either cursed or fortunate to live in a world with people far more intelligent than I, so I know many of you have likely already beaten me to the punch. You know what’s coming, so I won’t belabor this any longer. Here’s the scene that mattered to me. After a long time of languishing as a malnourished, beaten, isolated, and pathetic parasite, Gregor Samsa hears his sister playing the violin for some lodgers:

The family was entirely absorbed in the violin-playing; the lodgers, however, who first of all had stationed themselves, hands in pockets, much too close behind the music stand so that they could all have read the music, which must have bothered his sister, had soon retreated to the window, half whispering with downbent heads, and stayed there while his father turned an anxious eye on them. Indeed, they were making it more than obvious that they had been disappointed in their expectation of hearing good or enjoyable violin-playing, that they had had more than enough of the performance and only out of courtesy suffered a continued disturbance of their peace. From the way they all kept blowing the smoke of their cigars high in the air through nose and mouth one could divine their irritation. And yet Gregor’s sister was playing so beautifully. Her face leaned sideways, intently and sadly her eyes followed the notes of the music. Gregor crawled a little farther forward and lowered his head to the ground so that it might be possible for his eyes to meet hers. Was he an animal, that music had such an effect upon him? He felt as if the way were opening before him to the unknown nourishment he craved.

There are as many interpretations of that passage as there are editions of the story. But I have always liked the idea that this moment encapsulates the point Kafka was trying to make: the metamorphosis refers not only to Gregor Samsa’s (sudden) change into a bug, but to his family’s (gradual) change into something altogether inhuman. His father physically abuses him, his mother detests him, his sister begins neglecting his basic needs. And here, as the lodgers listen dismissively, taking for granted beautiful sounds from a beautiful instrument, Gregor is the only one who is attracted to the music. In fact, he is so attracted to it that he is willing to risk his safety in order to hear it better. It shows him that, despite his outward appearance, he is still human. At least that’s what Mr. Avalon told us.

“I wonder what she was playing?” he asked us. “Probably Jimmy Hendrix.” Mr. Avalon delighted in making absurdly incorrect statements for comedic effect. “Hendrix was a great American.” We might answer that it doesn’t really matter: Kafka doesn’t tell us, Gregor certainly couldn’t know, and the story isn’t titled “Sissy Plays the Fiddle”, so to ask about her repertoire choices is to get lost in the weeds of detail.

But still, what was she playing? Entire articles have been written conjecturing what kind of bug Gregor was, or the exact layout of the apartment in which he lived. Why should the matter of the sister’s music be any less important? Maybe it was an arrangement of something everyone would recognize, like the opening to Mendelssohn’s Concerto, Opus 64. Or perhaps it was the newly popular Liebesleid by Fritz Kreisler. But my money is on J. S. Bach’s famous Chaconne in d minor from his Partita, BWV 1004. If you’ll forgive the conceit, I’d like to tell you why.

I have my reasons for picking that particular piece. Firstly, there are clues in the story. The sister’s skill is developed enough for her to consider enrolling in a conservatory, so she’s not likely playing “Hot Cross Buns” or “Baby Shark”. Instead, she should be learning some Good, Proper, German Music™, and Bach would fit that description exceptionally well in 1915 Prague. She’s playing truly solo violin, with no accompaniment. That eliminates a surprising amount of the repertoire. Then there’s the matter of her eyes, reading the music “intently and sadly”. Her performance must not only be highly involved, but emotionally taxing as well. The three lodgers provide a clue, too: They tire of the music, and what began as excitement turns to bored obligation. The chaconne is a 15 to 17 minute long essay on a single chord progression, a work that offers profound beauty but demands concentration and emotional maturity in return, two traits that the lodgers, fastidious though they seem, obviously lack.

Funny, isn’t it? The bug is the only listener in the room who remains captivated by the beauty of the music.

More importantly, however, is the pathos of the music itself. The first few measures waste no time in announcing to us that this work will have quite the emotional heft. Stubborn tradition tells us that Sebastian Bach composed the chaconne as an outpouring of grief after the death of his first wife, Maria Barbara. That is, unfortunately, almost certainly not the case; music as a means of self expression was a foreign concept to a High Baroque composer like Bach. But, as the old saying goes, it’s such a compelling idea that if didn’t really happen, we would have to invent the story ourselves. After all, the variation structure of the music lends itself to ruminations on loss and desolation–

–but ruminating on loss and desolation would lead me back to thoughts of Mr. Avalon, or our good friend Fred Bell, or old family road trips, or any number of other people, things, or experiences that are gone now. And that, of course, leads me to ruminate on any number of other people, things, or experiences that will be gone one day. And it’s much more pleasant to get lost in the weeds of those details, of Bach and violins and what Gregor’s sister was playing that night. Thinking on music can be a glorious distraction sometimes.

Maybe that’s what Gregor was doing that night, as he moved closer to his sister as she bowed the strings and swayed to the rhythms. Maybe he wanted—needed—a righteous distraction from the pain of his world. For a moment, as he was confronted with his humanity one last time, he forgot about the filth in his room, the festering wound on his back, his father’s hatred. Wouldn’t that be beautiful? The loss in the music just might have sheltered Gregor from being overwhelmed by the loss in his life.

Of course, many reading this are likely to object. Music isn’t a distraction. It can be, and very often is, a direct confrontation. If music didn’t confront, it wouldn’t offend. In “The Metamorphosis”, it confronted Gregor with the ultimate question: “Am I human, after all?” But then, after the confrontation, the music blessed him with well-deserved distraction. It was a distraction that caused Gregor to forget himself. He needed to be close to the music. All other concerns were secondary. If he was still human, he could weather the pain yet to come. He might be chased out of the room, dying alone, but he would die with the dignity of his humanity. And what did the music do? It showed him that humanity one last time.

If you knew the man, pour one out for Mr. Avalon. If you didn’t, reminisce about a loved one. Wrap yourself up in the beauty of this magnificent piece. Allow the music to confront you with loss, with ultimate questions, and then allow that same music to distract you. For just a few minutes, crawl your way to the sounds of this violin and let there just be the music.

Leave a comment